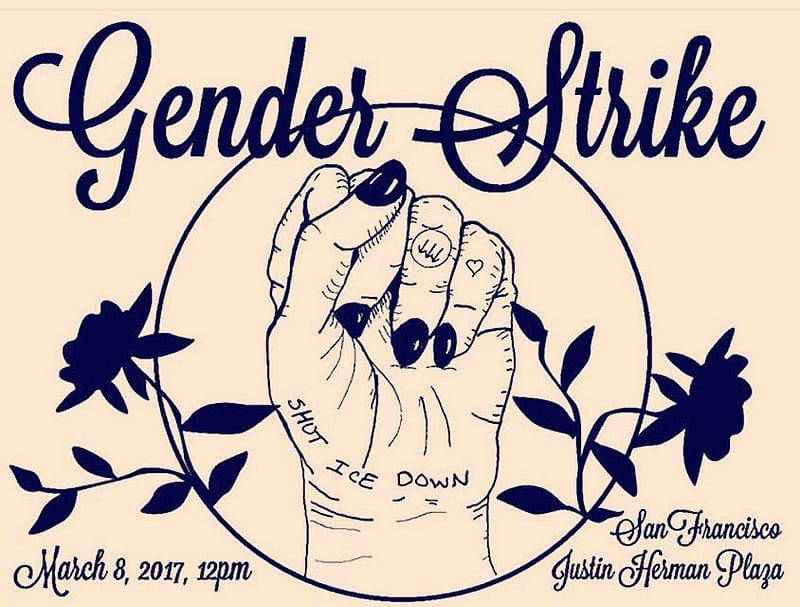

San Francisco Gender Strike speech

When I first heard about the Gender Strike, my first reaction was “great, finally a day I can do zero emotional labor”. Then I laughed, and then I cried.

The other femmes in the audience know what I’m talking about.

But I’m here. Because, dialectic on the assumed 24/7 availability of femme labor aside, I am here because I have the privilege to be here. I am white, I am cisgender, I am abled enough physically and mentally to be able to stand here speaking to this crowd.

I am privileged to have a job that is flexible enough to allow me to be here during the work day. I am gifted with a life where I can feel relatively safe protesting, where I can be out about my experience as a sex worker.

I came here today in part to remind you of the many people who cannot afford to be here, to speak about sex work as a reminder of many who are prevented from doing so by social stigma and legal consequences.

I speak from my own experiences, and in appreciation of the sex workers, many of whom were Black, brown, queer, and trans, who have fought so hard for people like me to have spaces to exist.

I’ve been all over the sex industry, from nude modeling and escorting to working as a Dominatrix and as a porn performer. As such, I’m often asked if sex work empowers me, if it’s safe, or if I feel morally corrupted by it.

I have never been asked these questions in reference to working as an unpaid intern. I’ve never been asked that about my job—both underpaid and overworked—in the marketing department of an athletic company. I’ve never been asked that about working retail—a job where sexual harassment was routine and reporting it could get you fired.

I’m only ever asked about my working conditions, my financial security, and my health on the job when the job in question is sex work.

Financial security is not something my generation or class has grown to expect. Like an oasis, it looks luxurious and attainable, yet somehow always remains just out of reach. Being a sex worker allowed me space to breathe—the ability to put money into a savings account while going to school. Yes, I felt empowered by financial success. Yet as long as the only industry where women consistently earn more than men carries such stigma—and even then, this is only as performers, not as producers or distributors—and as long as we live under a capitalist patriarchy, I have to question how empowering sex work can really be.

But not because of the nature of the work itself, or because it involves sex—it’s far more complex than that.

I think it’s the stigma that prevents sex work from being empowering—a stigma that long outlives your sex work career. You can be fired if you are found out to be naked on the internet. You can lose your apartment, or your kids, or your lover. You and your family can be threatened with deportation if discovered. You can lose your privacy, have your name and address posted for people to harass you … and people will say you deserved it.

Unlike any other job, where you are allowed to change careers, society brands sex workers for life. And this impact disproportionally hurts the most marginalized among us - trans women, Black and brown folks, immigrants, people with disabilities, and single mothers.

The same people who consume pornography still say they would never want their daughters to do it because ultimately, we as a culture still believe that porn performers are “those” kinds of women—not ivy league students, not loving mothers, not business owners. Sex work may empower some and humiliate others, or we might start feeling one way and eventually feel another. This also holds true for food service, though we ask that question far less often. Yet stigma against so-called “sluts” actively prevents sex workers from being able to do other work, even when they want to.

Work, of any kind, is only as empowering as the amount of agency the employees have. Sex work is no different, hence we need rights … not rescue. I wish anti-sex work feminists would address that side of the issue, rather than just pushing women to quit the only job willing to pay a living wage without an exit plan. We need to look, honestly, at how we treat "labor."

“Remember who the real enemy is,” is a takeaway phrase from the “Hunger Games” (I admit it, I watch problematic media). It’s something Katniss’ mentor says to her to remind her that the other Tributes are equally trapped in an abusive system, that the Capitol keeps the oppressed Districts fighting in the Games rather than fighting the Capitol in the streets. I see some real parallels to that in feminism, and it kills me. I see the morals and assumptions of mainstream patriarchy in the transmisogyny I witness among some feminists, I see it in the racism of who can come to a conference on feminist pornography, and I see it in who speaks over whom. We need to remember who the real enemy is, and make sure it’s not us simply due to defensiveness.

This isn’t just some feel-good bullshit meant to say “we should all hold hands and kumbaya” or whatever. This is about survival, pure and simple. Our critique needs to embrace aspects of sex positive AND sex negative feminism to be holistic in their nature and to save people’s lives. I agree with sex negative feminists that we cannot ignore how mainstream pornography is problematically marketed, what acts are featured above others, who is shown and how, and the entitlement that can come of male privilege. I agree with sex positive feminists that we cannot ignore how big business ensures via payment processors and terms of service that they continue to define the terms of what’s “normal” and what is deviant, we cannot ignore issues of representation or the stigma of female sexual pleasure. I’m also aware of how the Nordic Model and the stigma it reinforced lay the groundwork for the death of Petite Jasmine, even as proponents of it claimed criminalizing johns was for the safety of women. This isn’t just academic theory, tossed around a classroom. The longer we go without addressing issues raised by both the sex positive and the sex negative camps, the longer the uninformed public will throw their support behind things like “Real Men Don’t Buy Women” or rescue organizations that offer religious propaganda rather than childcare, GED assistance or places to live.

Feminist sex work excites me because I think it offers a response to both areas of concern in a practical, financially sustainable way … or it could. I don’t think anyone in the sex industry (even the feminist porn industry) could say honestly there’s nothing fucked up going on in some areas. We cannot be afraid of criticism. We should instead welcome it. We need to see being called out as a moment to check in with ourselves, to seek out the voices of the marginalized in our communities and to listen. We need to acknowledge that if we are genuine about wanting to hear from less privileged feminists, we need to make it worth their while to take time off work to educate us (and yes, I mean pay them, among other things). I do not believe the sex worker rights movement or feminism as a whole will succeed if we do not create and encourage space for challenging discourse, and if we, as privileged feminists, do not learn to take a step back and listen.

Additionally, we need to make space, safe space, for sex workers to have a bad day at work, to give consent without enthusiasm and have that respected, and to make hard choices. It’s easy to walk off a porn set when you know you’ll book another gig; it’s not so easy when you waited months for this one and rent needs to be paid. And women are expected to provide emotional labor for free on a daily basis. We are told to smile, to look pretty, to be nice and not angry, to be compassionate and not cold. We are punished if we do not respond receptively to catcalls, sometimes with violence, sometimes with death. We cannot respond to this external violence by doing this to ourselves, and insist that women in particular perform arbitrarily “appropriate” responses to their desires or sexual behavior in order to fit a mold of “Good Feminism.” And we certainly should not blame those people who decide that if they are going to be pushed to provide said labor that they should be paid for their work.

Why do you need sex workers to be either empowered or degraded? We don’t ask most employees to pick sides, because we understand that relationships to jobs are complex. We might like the money and hate our coworkers, or love our coworkers but hate the pay. We might love our work but hate the impact it has on our relationships. We might have fun sometimes, and wish we could be anywhere else at other times. Life’s complicated like that, especially under white supremacy, capitalism and patriarchy.

Comments ()