Burning Man: A Lesson in Impermanence or Obduracy?

I went to my first Burning Man in 2005. I went with a friend’s theme camp and was part of a community of artists who made sure I was prepared for the week-long festival of connection, ingenuity, chaos, and resilience. Many of the people I spent time with were old heads who had already been coming for years, and were excited to show a virgin Burner the ropes even while good-naturedly complaining about how it “was better next year”. I pitched in with setting up, cooked a camp meal, and explored the art, music, and community with wild abandon. I certainly found it thrilling, unlike anything I had experienced before (and I’m sure that the psilocybin didn’t hurt, either!)

There was something so powerful coming from a world where I didn’t know my neighbors to one where talking to strangers was not only acceptable but encouraged, where vulnerability was admired, where playfulness was given leave to stretch its legs. Sure, you had to proceed with caution that you stayed hydrated and that you didn’t get TOO reckless on a piece of possibly dangerous art — the ticket warned that death WAS a possibility — but if you had a good head on your shoulders and allowed the magic to take you, you could have a transformative experience that could change the trajectory of your life.

That’s certainly what happened to me, but in my case, it wasn’t the dance music or the drugs that were the catalyst for my internal alchemical process. I mean, sure, I learned to be in the moment there, bouncing from experience to experience, and that was a helpful thing to learn. It also inspired me to keep giving back more every year I returned (which I did, 3 more times, working on a large art project, then volunteering at theme camps, and then helping to run one). Burning Man definitely helped me work on my patience and self-awareness, learning how to manage my physical and emotional needs under challenging circumstances. I did pick up some useful life skills on the playa. But that wasn’t the biggest spark that set my life alight.

It was that 2005 was the year of Hurricane Katrina. The hurricane struck hard and fast while we were in the desert, and on the ground, it was hard to know what was even happening in Louisiana. Cell phone service wasn’t easy to come by at that time — I think in order to check email, you had to go to Center Camp and check at a kiosk — but people began to brainstorm ways to help out as soon as information got to them. Camps got together supplies to send with groups of Burners who strategized on how they could use the skills they learned in a hostile environment like a desert in a place ravaged by disaster. Some folks left Black Rock City and went straight to the Gulf Coast to pitch in. Burners Without Borders was formed.

Sure, the art was cool, but that swelling of community care? That shift of gears from having a good time to mutual aid? That was inspiring to me on a whole other level. It was at that moment that I realized that I wanted to find new ways to bring the togetherness, resilience, and excitement I felt at Burning Man to projects locally in accessible ways. That first Burning Man inspired me in ways that would be a guiding principle in my life for the next almost 19 years. Mutual aid became my higher power.

Imagine my surprise to find that energy falling away with each subsequent time I went to Black Rock City. People wanted to do drugs, dance, and fuck, they came here to escape the harshness of the “default world”, and they didn’t want to interrupt that with conversations about the environmental impact of their party, or how deeply concerning it was that consent was not deemed important enough to be one of the 10 Principles of Burning Man. I found myself horrified to discover that you couldn’t get a rape kit done on the playa, but instead had to drive back to Reno with a cop if you wanted to have one done — a 2–3 hour drive. In 2012, my last year, I held women who were avoiding an abusive ex and didn’t know who to turn to, or who had been sexually assaulted but felt confused about what they could do about it in such a strange environment — both a city of over 70,000, and yet not, because it was all temporary and transient. Add to that a community increasingly suspicious of strangers, as undercover cops prowled trying to ticket and arrest people for drugs, and it didn’t feel like it used to. I stopped feeling a fear of missing out, and instead turned my attention to art collectives and mutual aid projects in my local community.

I’ve done a lot of mutual aid work over the last 12 years, and I’ve rarely met someone in the trenches with me who currently self-identifies as “a Burner’. This isn’t to say that people aren’t taking that Burning Man spark and finding ways to light it in their home communities. Burners Without Borders continues to offer microgrants and steward projects that are sorely needed, from sanitation and hygiene improvement in Uganda to providing backpacks full of supplies to unhoused people to food drives for local indigenous tribes. It’s amazing to see people taking their passion and injecting it back into communities that have been too long operating from a place of lack. But living in the Bay Area, where Burning Man was born, I would have expected to see more of a drive to fund local art projects, engage neighborhoods with skill shares and block parties, and share resources like bikes, tents, and food.

I think part of the reason for this shift is that it increasingly feels like Burning Man isn’t for artists or art anymore. There’s less of a focus on participating and more of a drive to be seen there. Plug-and-play camps have existed for years, but with social media leading the charge, there are more and more wealthy people going to Black Rock City, not to contribute, but to consume. Now, you can stay in a luxury camp for $20,000, get served food by Michelin chefs, fly in on your private jet (the fact that this article lists a bunch of ways to “experience Burning Man in luxury”, and then bookends it with an insistence that it’s not about commodification, really underlines the absurdity to me). The fact that celebrity camps even exist is mind-boggling to me. Would these rich and famous people get their hands dirty setting up tents for their campmates, or lugging water to donate to people traveling to a disaster zone? I doubt it.

Burning Man feels like it’s become a place for people who think “self-reliance” includes a personal chef, who don’t need money on the playa because they’ve already spent more than most people I know earn in a year. It’s a place that claims to care about community but still held a super spreader event in 2022, sharing Covid and monkeypox with their local communities after the Burn. Is this really what it’s about?

So when I saw the announcement before the Burn this year that Burning Man couldn’t sell out their tickets, for the first time since 2011, I admit I felt some schadenfreude. Oh well, right? The people who made Black Rock City happen, who ran theme camps to delight others, who built art to inspire… well, they can’t afford the $575 ticket, never mind the camping gear, the food and water, the transportation, the camp fees, etc etc etc. It looked like maybe, finally, people were beginning to say “you know what, fuck this actually”. And why not? For an event that cared so much about self-reliance, they certainly seemed to demand a lot from the volunteers that made it happen. And it’s a problem for staff, too. The fact that the Black Rock City DPW has a staggering suicide rate, and that the Burning Man org appears to union bust, says to me that maybe this party isn’t worth the cost of admission — the financial cost, the cost to the planet, and the cost to the people who pour their sweat and blood into it.

Imagine my absolute shock when, instead of taking some time to reflect on how this was not sustainable and changing the way the festival works accordingly, the Burning Man CEO put out a request… for donations. Donations to the tune of $20 MILLION DOLLARS. According to Google, a Burning Man top executive makes $244,253 per year, but I don’t see them taking a pay cut to help make this happen. Sounds like maybe the Org needs to take their principles to heart and be more radically self-reliant, no? The self-importance of a festival to ask for donations during a time where the world is plagued with genocides and a Christofascist is trying to overthrow our government is WILD to me. It feels like an example writ large about the issue with libertarianism — it collapses in on itself because it’s just not sustainable, especially when pushed up against climate change, unstable and underexamined power dynamics, and increased financial disparity.

It sucks, because there are people dear to me and mine who are employed year-round by Burning Man, and I don’t want to see them lose their jobs. On the other hand, I keep coming back to the question — if Burning Man didn’t take up so much of their time and lives, what amazing stuff would they feel called to make? Is Burning Man still driving them (and us) forward? Or is it an albatross, holding us back from taking wild steps into the unknown?

In her letter to the Burning Man community, CEO Marion Goodell said “The world needs what we offer now more than ever.” But… do we? At least, do we need that energy, those resources, to go to Black Rock City? Maybe “radical self-reliance” was never sustainable, because we are a community, and we need each other! Maybe it was a terrible idea to create a festival where substance use and sexual freedom were encouraged, but where consent wasn’t even one of the 10 principles. Maybe Burning Man began to serve a different purpose when undercover police looking to bag people made strangers suspicious of each other.

It’s also not a failure to say that this did something remarkable, and it’s time for those seeds to spread. I don’t understand this desire to clutch to something that served an interesting and transformative purpose for quite some time, but has been increasingly less sustainable, and battling increased hostility from law enforcement. Why wouldn’t you want to take the lessons that you’ve learned, and the connections formed, and find new ways to do both of those things that didn’t require caving to the demands of law enforcement, or had such an intense impact on the land? It just feels like it’s an ego thing, and I feel like that’s the antithesis of what I loved about Burning Man.

Is there something valuable there, still? Maybe. As jaded as I am, I think so. I know I would get involved in the Burner community again if the focus was on using the skills learned from feeding theme camps to instead feed unhoused people. If we were constructing solar showers in disaster zones. If we were turning HIV testing vans into cool art cars that encouraged people to use these resources. I know a lot of people like me who burned out on Burning Man and instead starting looking at building experiences and wonder where they lived. I know my town is trying to figure out how to build and fund dog runs for local homeless shelters. Imagine if we built those and made them look cool as well as sturdy, instead of building something just to burn?

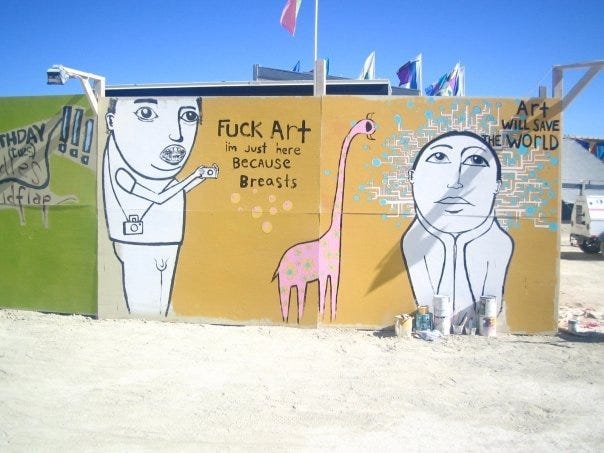

I’m not saying we don’t need art. In fact, I’m saying EVERYWHERE needs art, badly. We need to be thrilled, and challenged, to giggle and puzzle out meaning, to introduce ourselves to our neighbors and share our noodles and tools. We need the inventiveness that comes from being exposed to art, and we need it to not be gate-kept behind a trash fence. Perhaps keeping so much of that beauty and weirdness and acceptance and funneling it into a city that exists for one week out of the year is doing the “default world” a major disservice.

I look at my experiences of Burning Man, and I look at what I’ve learned since, about how communities come together during disasters to help each other, the inventiveness of mutual aid, the fierce love that comes from creative collaboration. Some of my favorite community projects were birthed, grew, and withered in the years since I stopped going to Burning Man, but while I look back fondly at those times, I don’t feel bitter about them coming to a close. Sometimes, you have to accept that everything has a life cycle, and instead of trying to drag it out to the bitter end, you can joyfully use the seeds to grow new and spectacular things.

I wonder what would happen if Burning Man just… died, and we let it go. Isn’t that the ultimate lesson of Black Rock City? Impermanence? Accepting change? Perhaps it’s time to embody the Fool tarot card, and step off the ledge of what we know. I learned that courage at Burning Man, and I can’t wait to see what grows from its ashes.

Comments ()