As a Sex Worker, I Didn’t Feel Exploited

My first job was working at a daycare for a few hours after school a few times a week. I helped put out snacks, wiped away tears, read them stories, helped with their craft projects. I was 17, and glad to do something with my time that I hoped would help me with employment further down the line. It was unpaid. No one blinked an eye.

My second job was working retail at the mall. I had to walk for an hour and a half to get to work, and an hour and a half to get back because the bus cost $2 each way even if you were low income. Sometimes, I walked in the snow. Often, I walked home in the dark. I was 18 and already eating at the mercy of food pantries since I could only get four hours of work per day a couple of days a week. Otherwise, the company I worked for would have to pay me health insurance. I was paid the minimum wage of $6.75. When I left that company five years later, having transferred to another state, I was making $7.25. Eventually, I took on another job, also at the mall, to make the walk worth it. Over the holidays, I worked yet another job, ensuring I was working 7 days a week, usually 2 jobs a day. I still wasn’t making enough to consistently pay rent after taxes.

Then I became a sex worker.

I started as a professional dominatrix, which meant that I spanked men and got paid more for an hour of work than I used to be paid for a week’s worth of work. The first place I worked was a house with a madam, who booked the clients, told us what to wear and how to act. Everyone was expected to wear nylons, black pumps, and black lingerie, with a full face of makeup. I appreciated the security of working in a place with other people but disliked the uniform. I quit after a month to go off on my own as an independent sex worker, using Craigslist to book my clients and talking to other sex workers about safety precautions. I was 20, my own boss, setting my rates myself and working on an as-needed basis.

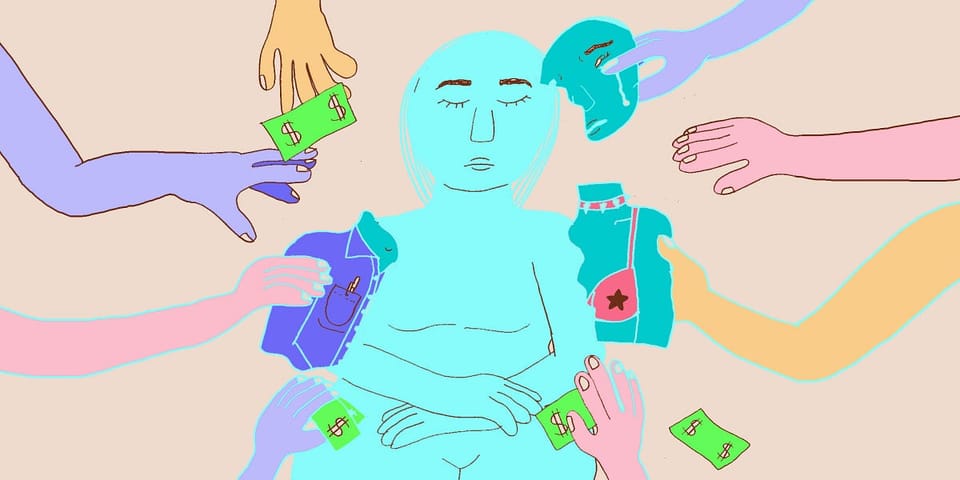

This is the point where people began to express concern that I was being exploited.

I think this is important to take a moment to consider. We are aware that most entry-level jobs are inherently exploitative. It’s the nature of the beast, we say. When you start as a worker, you will be underpaid and overworked. Many industries rely on unpaid internships, and many of those unpaid internships are illegal. Fight for your rights, though, and you’ll potentially be blacklisted from the industry as being difficult to work with, thus negating the work you’ve already done.

We grow up with narratives that tell us, even as children, that if we work hard, are nice to those who have more power than us, and toe the line, we will be rewarded. Eventually. One example of this includes The Little Engine that Could, where a small engine (often coded as female) agrees to try and shoulder the load of a much more powerful train and manages to do it with optimism and hard work with the reward simply being the self-satisfaction of a job well done. Cinderella is a story of a girl whose father marries an abusive woman, and through years of doing whatever her stepmother demands, putting up with abuse without complaint, and humble prayer, she manages to magically get a beautiful dress, go to the ball, and woo a Prince. Annie and Oliver! both conclude with an optimistic downtrodden orphan getting adopted by a rich person. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is ultimately about getting lucky, that if you are good, honest, and not opportunistic, you may go from rags to riches.

We grow up with narratives that tell us, even as children, that if we work hard, are nice to those who have more power than us, and toe the line, we will be rewarded.

It’s within these stories that we teach people, and children especially, that exploitation is to be expected, and if you bear it cheerfully and without question, you might get rewarded in the end. The keyword here is might. We never hear about all of the other children in poverty in Charlie Bucket’s world, who did not get a golden ticket and did not inherit a successful factory from a questionable benefactor. We don’t really get the story of the Oompa Loompas, and never from them — only through WIlly Wonka’s interpretation of events, where he rescued them from a hostile land and they’re happy to be paid in cocoa beans. Are they, in fact, perfectly happy to be locked in a factory in England, providing capital to a wealthy businessman? We’ll never know, and we’re expected not to ask.

One lesson you could take from this is that it’s ok to exploit some people. Often the people it’s ok to exploit end up being women, people of color, people with disabilities, undereducated people, immigrants. You might also get the message that it’s unavoidable to exploit some people, and that exploitation is some sort of automatic default state. If we are exploited, we’re told, it’s on us to improve our lot by working twice as hard. And keep your head down.

As a sex worker, when you’re told about your exploitation, what they mean is what they read in the news and what they see in the movies. They equate sex work with human trafficking. They mean that you “sell your body” when you have sex for cash, that you value sex less if you do it for money than if you do it for free. Having sex for pleasure, having sex to please your partner, having sex to increase intimacy, these are all typically seen as valid reasons, fair exchanges. Sex for money, though, is different, even if you’re setting the rules of engagement. I was not lectured about selling my body when I was standing for eight hours a day, damaging my body through repetitive motions in ways that have left me disabled now. I am allowed to sell my body if it’s for a lot less money. I am allowed to have sex if it’s for free.

Which is not to say that I didn’t experience intense exploitation within the world of sex work. I saw it when trying to help fellow sex workers report being raped, in how the police (and the public) responded to them. I saw it in how clients felt entitled to respond with violent threats if I said no to them, knowing I couldn’t go to the cops. I saw it when I was told that if I wanted to have any success as a porn performer, I had to accept sexual scenarios I was ethically against, and I had to stop talking about racism, misogyny, and transphobia within the industry. I saw it when my ex-boss at an adult company tried to have me socially blacklisted for going public about their workplace abuses. I saw it when abolition groups were privileged in conversations about the legality of sex work and spoke over sex workers and their experiences. I saw it in how church groups claiming to want to support sex workers used the money to line their own pockets, offering sex workers cupcakes and eyeshadow instead of job training and rent money so they could change careers if they wanted to. Yes, sex work can be exploitative, but perhaps that has more to do with the exploitation of low-level workers in industries that lack unionized protections, and the exploitation of minorities to fundraise for things those minorities don’t even want or need.

When retail felt too exploitative, I quit and became a sex worker. When sex work felt too exploitative, I quit and became a writer.

As a freelance writer who has been typecast as a writer of intensely personal stories, I have found myself locked into a new cage. If I want to get my pitches accepted, I must write about some of the most difficult times of my life, and make it clickbait. I have to be wary of nuance because anything other than full conviction leaves me and my rawness open to vitriolic harassment. If the platform I’m writing for disagrees with my conclusions, I may find the piece canceled, often without a kill fee. “Hope you find somewhere else to place this!” the editor will say, knowing full well how difficult that is when you have written a piece in the voice of one brand. More often than not, your labor will have been for free, or well below minimum wage. And so, you tell the stories they want to hear, not the ones you want to tell.

What amuses me (in a bitter sort of way) is that most often, it is my pieces on sex work that gets the biggest reaction from those who want to save me from exploitation. While a woman who has never been a sex worker tells me what I should be doing with my body, and how I should be emotionally affected by it, she does not ask any questions about how much money I’m making writing the piece. She doesn’t ask if I have insurance now. She doesn’t ask about the impact on my body that staring at a screen has, or sitting at a desk. She doesn’t ask me if I have worker protections. Some exploitation, after all, is acceptable and/or inevitable.

As a freelance writer, I don’t get benefits. My contracts can be canceled on a whim. I often get paid months after I invoice, and sometimes my articles sit for weeks without being edited. Sometimes, my pitches don’t get accepted and I discover a very similar article on the site I pitched to, weeks later, written by a staff writer. There is no recourse to this, it’s just a risk of the job. I am usually paid between $125 and $300 for a lifestyle piece, which on average takes me 6 hours to write and research, and another 6 hours at least in editing/rewrites. That makes my hourly rate $10–25 an hour before taxes. As an independent contractor, I will then pay more in taxes than I would if I was an employee.

That’s just the practical stuff, of course. It’s harder to measure emotional exploitation. What’s the cost of rehashing trauma for the sake of a stronger piece? How do you put a cost on the impact it has to write about the kind of gripping personal experiences people want to read and editors want to publish? For years, I wrote about sexual assault, often being asked to talk about my own experiences to make the piece “juicy”. If I wanted to get paid, I had to consent on some level to triggering my own trauma. Sometimes I could persuade myself it was for the greater good (because these stories needed to be told) and sometimes, I knew it was just because people love to rubberneck a car crash. In these situations, who is doing the exploiting? The editor, pushing me to share more? The reader, for clicking on these articles? Me, for saying yes to doing it in the first place? The advertising companies preferring to put their ads on sites with more viral content? The CEOs of these companies, who try to get as much out of their workers as possible while paying as little as possible? All of the above?

More to the point, once you understand that you’re being exploited by whichever industry, what exactly can you do about it? Usually, quitting for a better job is not an option so much as it’s a pipe dream. Googling “stop being exploited at work” pulls up articles more interested in how to stop being a people pleaser, focused on the individual instead of the working conditions. But here’s what I’ve learned — more often than not, it’s not “this boss”, but *all bosses*. It’s not “this industry”, but all industries. So, in order to combat this widespread exploitation that underpins our society and way of life, I strongly believe we need to be invested in all workers rights, not just our own.

There’s different ways to do this, though many of them have seen workers punished by their employers for utilizing them. Across the writing industry, people have been trying to unionize to offer more security, though with mixed success. For every story like Vox Media or Vice managing to unionize, there are stories like Hearst, who recently set up a website dedicated to persuading its workers not to unionize, or Mic, who was bought out by Bustle and their unionized workers subsequently fired.

Those unions typically only protect employees, anyway, not the freelancers that often make up the majority of the content created on these sites. For freelancers, sharing rates and work experiences amongst ourselves helps to keep sites accountable to who they employ and how they treat workers, and can encourage marginalized people to negotiate for higher pay. We tell each other who pays on time, who ghosts writers mid-story, who will offer a kill fee. This collective information sharing puts freelancers in a position of more power when negotiating their contracts. There’s also the IWW Freelance Journalists Union, which hopes to offer some of that solidarity and practical support to non-employees.

While these measures help mitigate some of the consequences of an inherently exploitative society, it doesn’t mean those consequences don’t still exist. Many industries still rely on unpaid or underpaid intern labor, while violating labor laws on what those interns are expected to do. It’s still considered normal for entry-level work to be paid at an amount that leaves the worker below the poverty line, even though many people find themselves unable to progress past entry-level positions. Personal, individual values like working hard and staying cheerful does not make up for the vast disparity we deal with on a day to day basis, and ultimately, many of us only choose what sorts of exploitation we are willing to accept.

The way industry works right now is exploiting the majority, whether you work in retail, as a sex worker, or as a writer. While some economists think the way to fix that is through the free market and capitalism, others believe that it’s through increasing and bolstering the welfare system. I’m just tired of being told what exploitation is by people using me and my stories to make some point while leaving me out of the conversation. If you want to end exploitation, do it by listening to the exploited.

Comments ()